Speak up, be heard: what COVID, anxiety and Cambodia have to do with changing voice services

Phone calls are out – and yet, voice is reaching new levels of popularity. What’s driving this change in how we communicate? And why is Cambodia responsible for half of all Facebook Messenger calls?

Back in 1995, Bob Hoskins told us in his distinctive Cockney growl, “It’s good to talk”, in a famous TV advert for the UK’s incumbent telco, BT.

Over 20 years later though, in 2017, the number of mobile calls made in the UK fell for the first time ever, a portent of doom for the telco industry as worldwide voice revenues are expected to drop by as much as 45% by 2024. As data traffic has grown exponentially, plain old voice has had an inverse slide downward.

At the beginning of lockdown in the UK, time spent talking on mobiles rose by almost 50% from an average of three minutes and 40 seconds to nearly five and a half minutes per call, according to Ofcom. Despite this, the number of calls being made remained unchanged, with 22% of people not making a “traditional” call from their mobile at all.

What’s behind the long-term fall in calls?

The growing number of nuisance calls could be to blame, as even scammers adjust to WFH. Almost 90% of respondents to a YouGov survey reportedly refuse to pick up calls from unknown numbers.

But even when friends & family are on the line, millennials – typically considered power users – are reluctant to pick up, despite being largely inseparable from their mobile devices.

This attitude extends to the workplace too, according to a 2019 survey of UK office staff, which found that 76% of millennial workers get anxious when their phone rings compared with 40% of baby boomers; in fact, 61% of millennials actively avoid making or taking calls.

Major reasons cited include “confrontation, being overheard, having no paper trail to backup conversations and fear that they wouldn’t be able to understand the caller on the line.”

Though this digital-native generation has grown up with more means of non-verbal communication than ever, much of the blame for this shift has been placed on social anxiety, which has seen a massive increase in cases over recent years, particularly in the young, who naturally gravitate towards the non-intrusiveness of text, email or social media messaging as a result.

However, whether as a result of anxiety or otherwise, when it comes to mobile phones, discretion is king for many, and taking a phone call around others or in public is at odds with this attitude. But smartphones and OTT services have not, as some would argue, “killed the art of conversation.” Voice is simply changing.

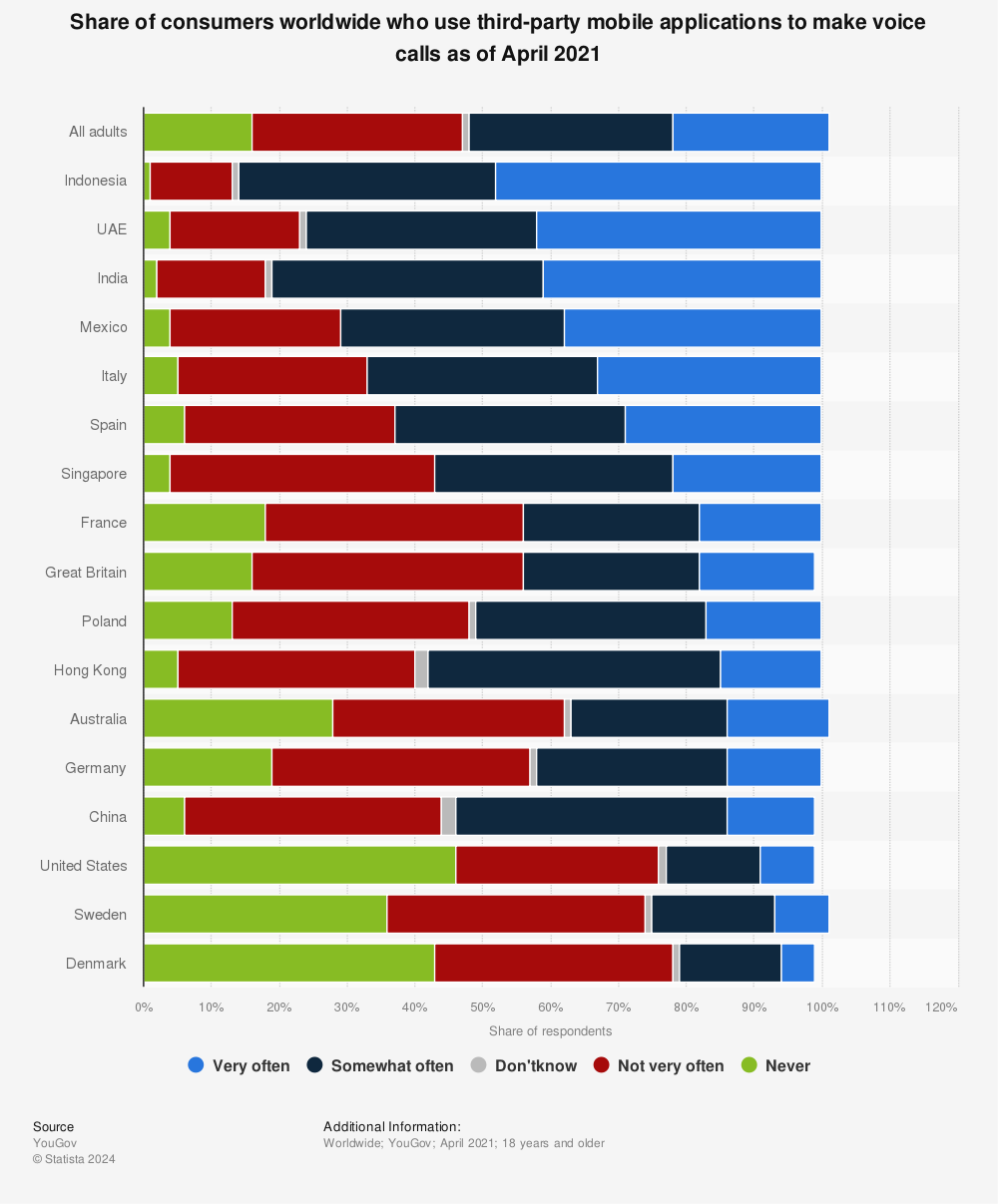

OTT services have precipitated the biggest fall in traditional voice, as the likes of WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Zoom, Skype, and others, have enabled users to make free or massively discounted calls via the Internet. Five billion monthly OTT users globally made one trillion minutes of OTT calls in 2019, compared with just 432 billion minutes of traditional voice traffic.

A study of voice notes in Germany [link in German] found that 32% of users send voice messages several times a week, and 69% occasionally, citing convenience and fewer misunderstandings as major reasons.

Now a staple of all major messaging platforms, voice functionality is spreading to other apps too. Twitter introduced voice notes in 2020, letting users record short clips to publish as tweets or messages, while dating app Hinge introduced audio answers for question prompts earlier this year, letting users post audio clips to their profiles and send voice notes in chats.

Furthermore, an entirely audio-focused social platform, Clubhouse, launched in March 2020 on an invite-only basis initially, now boasting two million users and a billion-dollar valuation as of February 2021, as users starved of human contact flocked to hear from their friends.

Voice notes have even reached the music world, featuring extensively on a song from Adele’s latest album.

In fact, voice notes on many apps have enthralled users across the world; they’re big in countries such as Argentina, where users have to pay per message. But price isn’t the only factor affecting uptake; cultural differences play a huge part in the popularity of voice services too.

Despite only making up less than 1% of the world’s population, Cambodians account for nearly 50% of global voice traffic on Facebook’s Messenger app, as the complexity of the Khmer language means that most Cambodians find it simply too difficult and time-consuming to type.

It’s a similar story in China, where messaging app WeChat first launched voice notes in 2011, offering users a break from the not-insignificant task of typing in Chinese characters. More so than that, voice messages are a status symbol – a sign that the sender is a very important person with too little time to type. Users of WeChat now even have the option to convert voice notes into text.

However, some may find the convenience of voice notes overstated; they still show a disregard for where and when someone might be receiving a message, particularly depending on its content – if it’s a short message that could just as easily be typed out, the recipient of your message may not be so thrilled to hear you say just “okay!”

Of those quizzed in the aforementioned German survey, 40% state that listening to voice messages takes too long (being such a verbose language doesn’t help when messaging one’s Lebensabschnittpartner), and 17% said that recording voice messages simply makes you look “stupid.”

What’s more, many of us just don’t like the sound of our own voice!

Moreover, voice notes are not even any more secure than text, with Facebook and others having been caught accessing these messages without consent to improve their voice recognition software.

Faced with changing customer behaviour and the demise of traditional voice services, telcos must rethink how to position these new and emerging voice services alongside their traditional voice services, and what it will mean for their venerable pricing schemes.

As we’ve argued before, OTTs don’t have the monopoly on voice traffic, but telcos must be smart when it comes to pricing new services and bundles – not just offering unlimited voice and a hefty data allowance, but providing extra perks such as data sharing and family plans. After all, customers are willing to pay more for a better experience and strong brand bonding.