Does the Online Safety Bill spell the end for WhatsApp in the UK?

The Online Safety Bill is back, putting end-to-end encryption in the UK under risk in the name of child safety. Why could the bill lead to WhatsApp leaving the country, and is there another way to protect users and their private communications?

Making the UK “the safest place in the world to go online” by driving away every online service may sound like a pyrrhic course of action, but it’s a not-unthinkable outcome of the latest incarnation of the much-maligned Online Safety Bill, which threatens to leave Brits without access to many services, including WhatsApp.

This new version of the bill, which has gone through multiple incarnations in the hands of the UK’s many recent governments, puts the onus on tech firms with a significant number of UK users to monitor for and act against illegal content shared on their platforms. Expected to come into force in 2024, any non-compliant businesses risk a fine of £18 million, or up to 10% of global turnover.

Previously referred-to provisions against nebulously defined “legal but harmful content” have been scrapped; under a new “triple shield” approach, firms will instead be charged with removing material that is illegal or in breach of their own terms of service and provide users (both children and adults) with more tools to decide what content they see.

Further amends have added two-year jail sentences for social media company executives who are deemed to have failed in their duty of care, and the criminalisation of posting content related to illegal immigration which “show that activity in a positive light.”

Though there is no explicitly proposed ban on encryption contained within the bill, it is the requirement for providers to implement backdoor policies in order to be workable that would effectively be banning encryption by any another name.

In an open letter, WhatsApp, along with Signal, Viber, and other messaging platforms, has warned that the bill could “break end-to-end encryption, opening the door to routine, general and indiscriminate surveillance of personal messages,” leading them to bow out of the UK market.

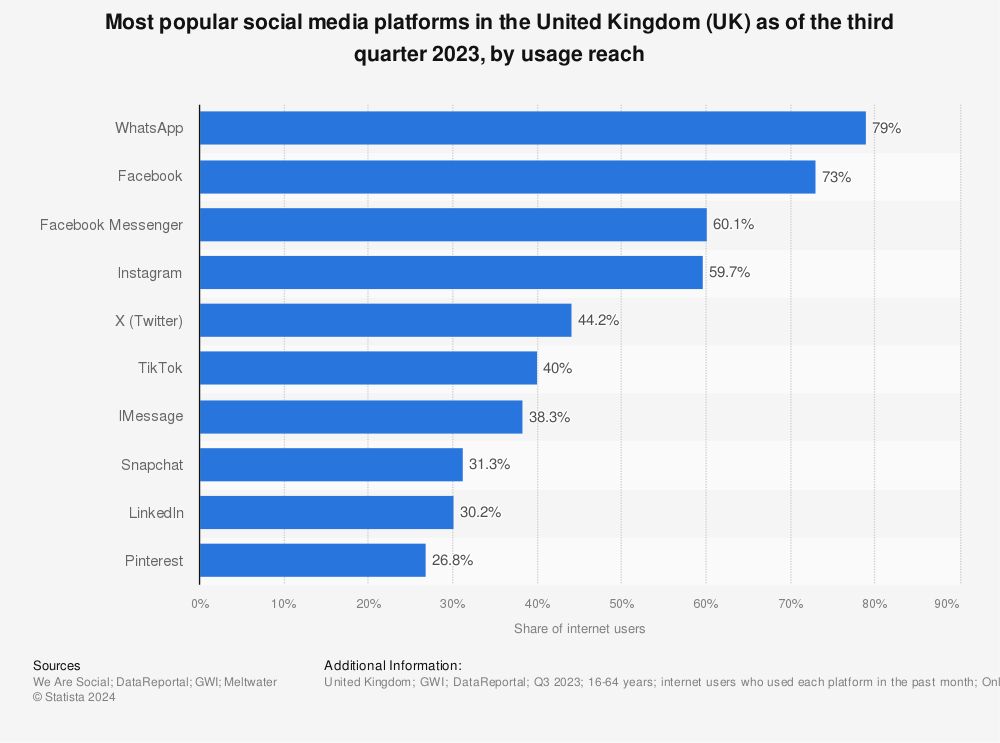

As the most popular messaging platform (or social media platform of any kind) in the UK, this would be a blow to tens of millions of daily WhatsApp users – not least the government itself, which has been accused of “government by WhatsApp”.

Under the bill, Ofcom can mandate companies with Section 104 notices to employ client-side scanning to inspect the contents of messages for images and videos (with “digital fingerprints” from a database supplied by the authorities) to identify illegal content before the contents of any message is encrypted and sent, flagging the user to the relevant authorities. It can also collect browsing information from users if they access WhatsApp via its web app.

Rather than pre-loading every device with this database, the comparison is performed on a server operated by the CSP or app provider, where the user’s data is visible to the provider, reducing the burden on the user’s device but increasing the “attack surface” of private messages.

These plans would effectively render end-to-end encryption (E2EE) null and void in the UK, cracking the contents of messages wide open for interception and interference from cybercriminals or state actors, or even for the government itself to indiscriminately repurpose as a “general mass-surveillance tool.”

The Index on Censorship has declared that the bill would give Ofcom “a wider remit on mass surveillance powers of UK citizens than the UK’s spy agencies… with less legal process or protections than GCHQ would need for a far more limited power.” While the abilities to access telecoms data afforded by the Investigatory Powers Act requires sign-off from a judge, following a ruling by the High Court last year, Ofcom’s Section 104 would be subject to no such limits.

Despite this, research by the NSPCC suggests there is in fact support among the public for scanning of private messages; 26% support it in all instances, but this rises dramatically to 70% when there is “reasonable suspicion” of criminal activity.

These numbers are, however, at odds with Ofcom’s admission that the bill “does not necessarily require that services are able to stop all instances of harmful content or assess every item,” and that ultimately, “Ofcom cannot compel them to remove it.”

The EU is also in the process of rolling out its own controversial “Chat Control” law, allowing governments to serve “detection orders” to companies, requiring them to scan any private messages, including email.

Canada has no such laws, but access can be obtained through court warrant; in a notable case from 2019, a court order was pursued to compel a suspect in a criminal case to provide the password to their phone, but the presiding judge declined the order on the grounds that it would be tantamount to the defendant incriminating themselves.

The FBI and Apple have long been at odds over the implementation of backdoors in iPhones. After a mass shooting in the US in 2015, the FBI controversially gained access to the deceased suspect’s iPhone (one set to delete its contents after ten failed passcode entries) by exploiting a zero-day flaw in the device; no messages relating to the incident were found.

US lawmakers have recently introduced the bipartisan Kids Online Safety Act. Though welcomed by some advocacy groups, others have warned the bill could in fact pose further danger to kids by curbing access to encrypted platforms, and subject online content to vicious culture wars already dictating what media children can access.

Sadly, no-one can be certain if the ambiguous wording of the Online Safety Bill as it currently stands is to give the authorities carte blanche to wield new powers as they see fit, or simply because they don’t have a clue.

Decisions on E2EE must consider the best interests of users without making it a zero-sum game between safety and privacy. Most platforms already employ robust terms of service, which outline what can and can’t be shared; the focus should remain on safe design and giving users options to moderate what they see, rather than censorship.

No-one doubts the importance of stemming the spread of harmful or illegal material shared online, however it must not come at the cost of user security.