Fair contribution: a fair deal for telecoms customers too?

Tensions between telcos and Big Tech companies are reaching fever pitch as CSPs demand fair compensation for their massive investments in infrastructure. We look at what Europe’s telecoms firms are asking for, and why them getting their way might not be the best outcome for customers.

The debate over the future of telecoms network funding in Europe continues to swirl, as major telcos continue to argue that big tech companies should contribute to infrastructure costs.

It’s not a popular idea among many in the industry; after all, car manufacturers like BMW are not expected to pay for the upkeep of roads per vehicle sold. But if half of all cars were BMWs, and the roads were in dire need of resurfacing, would attitudes be different?

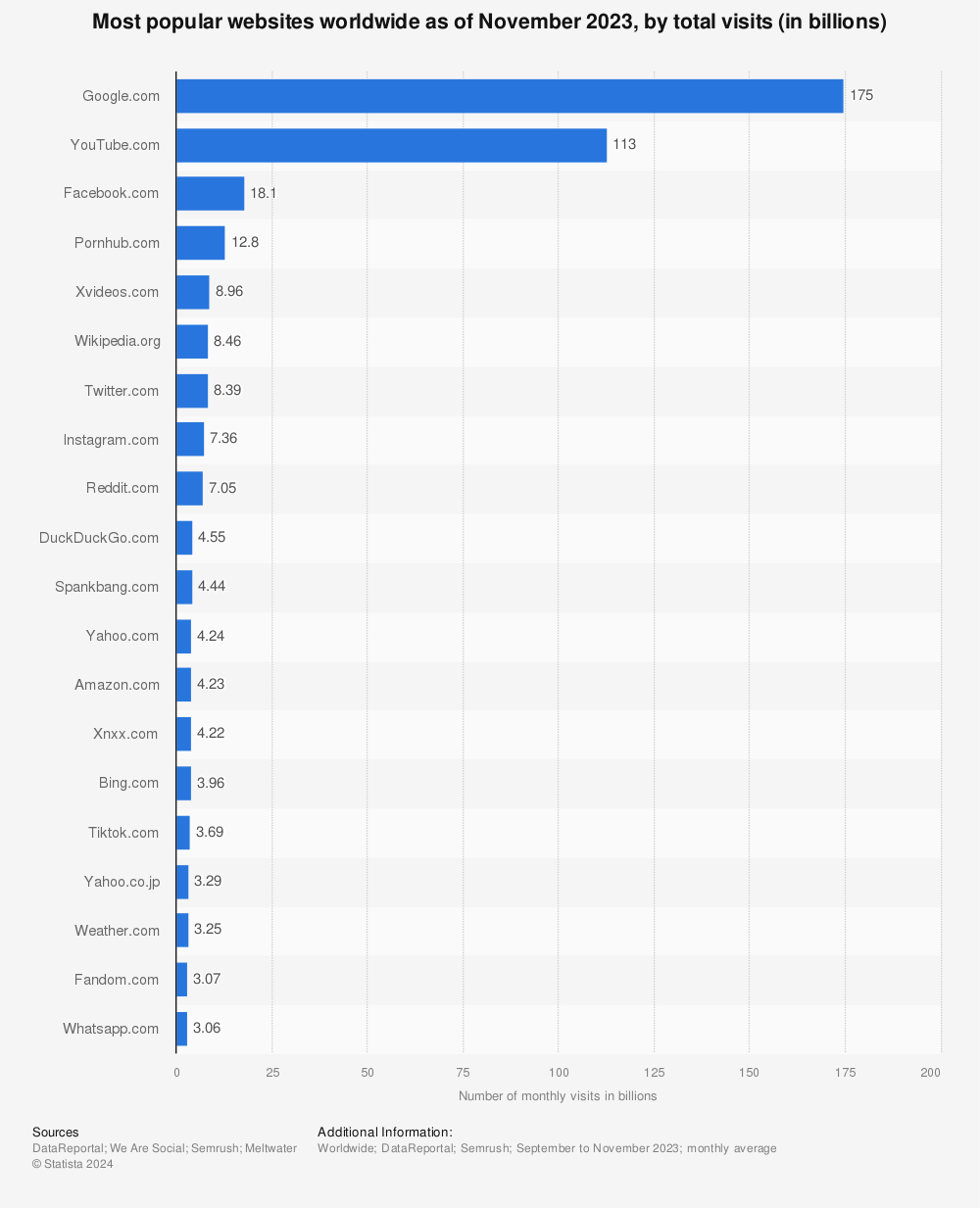

It’s a decade since so-called “FANG” companies were recognised as major players in the digital space, growing fat on profits off the back of infrastructure provided by telcos. Today, Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft and Netflix combined account for over half of all internet traffic, with Alphabet’s stalwarts Google and YouTube accounting for over 30% of all traffic.

Telcos have been offering more data at lower prices for years, as voice revenues are poised to drop by 45% to $208 billion by 2024 with customers continuing to adopt big tech OTT services instead, while facing high investment costs for upgrading and expanding network coverage to keep up with emerging data-intensive services. According to the European Telecommunications Network Operators’ Association (ETNO), the shortfall for European telecoms infrastructure stands at €174 billion.

Telcos now want any company accounting for more than 5% of their peak average internet traffic to pay their fair share towards infrastructure upgrades in Europe, given they’ve thrived on the foundation built – and largely paid for – by CSPs.

They argue that these giants would, at best, not reap the billions of dollars they generate annually, and at worst, not function at all. As one Orange executive said to CNBC, “Without the telcos, without the network, there is no Netflix, there is no Google.”

Based on a report by ETNO, traffic driven by big tech services generates up to €40 billion per year in costs for EU telcos. An investment of $30 billion could grow the continent’s GDP by up to €106 billion by 2025, create up to 1.26 million new jobs, improve QoS for customers, while reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions.

Certainly, big tech companies are not above making substantial investments in other firms to support their operations; last year, Meta announced a collaboration with Telefónica to form a Metaverse Innovation Hub in Madrid, the construction of a new data centre in Castilla La Mancha, and connecting Spain to new transatlantic and African underwater cables.

On top of investment requirements, telcos face the additional hurdle of regulation and oversight that big tech has long dodged in the name of innovation, although growing concerns over big tech’s handling of user privacy, misinformation, and harmful content could see them come under similar regulatory scrutiny.

However, some worry that making big tech pay could be detrimental to consumers, and threaten net neutrality. In a blog post, Markus Reinisch, Meta’s Vice President, Public Policy, Europe and Global Economic Policy, warned that charges would “ultimately hurt European businesses and consumers”.

The European Commission is now exploring whether internet giants should make a direct financial contribution to telco operators. However, in a new report, the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC) has come out in favour of tech firms.

The report argues that the provision of telecom infrastructure is generally a much safer, more profitable venture than the risky business of creating content, and the cost of network upgrades to handle growing data traffic is very low compared to the total network costs.

Most damningly, the report finds no evidence of network “free-riding” – quoting their own findings from 2012, BEREC cited “no evidence that operators’ network costs are already not fully covered and paid for in the Internet value chain.”

Content providers can instead optimise the data efficiency of their content and applications through edge computing or Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) to offset some of the costs of network upgrades. We saw this in action during the COVID pandemic, when Netflix and YouTube promised to throttle streaming quality so as to not cause the internet to collapse during those early months of quarantine.

In 2014, it was reported that Comcast was throttling the bandwidth of Netflix, resulting in degraded video quality for Comcast subscribers accessing Netflix. The pair soon struck a “peering agreement” to improve the streaming quality for Comcast subscribers. The agreement drew a mixed reaction; critics saw it as a departure from the principles of net neutrality, arguing that Netflix was essentially forced to pay Comcast for preferential treatment, but proponents said it was a practical solution to the congestion issues, and improved the streaming experience for Comcast customers.

South Korea’s SK Broadband, on the other hand, chose a less cordial path; following the global success of shows like 2021’s Squid Game, SK Broadband demanded that Netflix pays for the extra strain its shows were putting on networks.

As of 2020, the country’s Telecommunications Business Act requires national and international content providers to ensure a “convenient and stable” service to users, though does not specify that content providers must share network costs. Despite this disagreement, Netflix is still continuing to invest billions in new South Korean content.

While big tech undoubtedly benefits from the infrastructure, the consumer would ultimately be the loser if big tech is forced to pay – it’s hard to envision a scenario where firms wouldn’t just pass on these extra costs to consumers, or offer up lower quality services at the same price.

Telcos and big tech must recognise that, as the availability of one drives access to the other, and vice versa, they are dependent on the success of each other, whether they like it or not. Therefore, it’s in the interests of both to find ways to optimise network traffic and fund infrastructure upgrades through alternative models, such as public-private partnerships. This collaboration not only accelerates the deployment of cutting-edge technologies, but also ensures that the benefits are more evenly distributed among stakeholders.

As future telecoms networks move away from hardware, pivoting towards software-based as-a-Service models, it’s crucial for big tech companies to ensure fair contribution and collaboration in the development and maintenance of infrastructure.